The role of African narratives in the future of Artificial Intelligence

When the early European colonists set forth in the 15th century, the world was one to be conquered. Hundreds of years later, the advent of artificial intelligence (AI) marks the opportunity to imagine a different world: one to be nurtured, with systems founded on justice and equality. However, to get there, scholars argue, we need to deliberately centre the AI agenda on people, and ensure it is driven by all. Unsteered, humankind’s ship will not right its course towards a more equal world.

At a recent virtual workshop on African narratives of AI, digital policy researcher Chenai Chair argued that AI policies need to consider gendered realities and ensure that injustices are not replicated as we race towards a digital world. The workshop, co-hosted by the University of Cambridge and the HSRC as part of the Leverhulme Centre for the Future of Intelligence’s project on Global AI Narratives, brought together thinkers across sub-Saharan Africa to explore modalities and perceptions of AI in Africa today.

That same month, ahead of a conference on decolonial AI at Boston University, Sabelo Mhlambi argued similarly: “[I]f we don’t look at how...historic systems of inequality still persist, the AI systems will always reproduce the inequities.”

African states face a potentially paralysing dilemma with regards to their AI approach, said the University of Pretoria’s Professor Emma Ruttkamp-Bloem at the AI narratives workshop. Do they go all out and become a global role player with the eye on economic gains that AI offers? Or do they take time to stop and think about the social and ethical impact on vulnerable groups in their communities?

Although often seen as a dichotomy, the former might in fact require the latter. In addition to shaping innovation that promotes welfare, including diverse voices broadens our conception of artificial intelligence and expands possible futures.

AI Initiatives in Africa

At the HSRC webinar, MTN Nigeria’s Chief Transformation Officer Bayo Adekanmbi argued that AI needs to be shaped by pertinent issues. “So it's not just AI for AI’s sake, is not just data for data's sake,” said Adekanmbi, who is also the founder of Data Science Nigeria. The focus should be on developing AI that is applicable to poverty management, health diagnosis, education, and microfinance.

On her newly-launched site, My data Africa, Chair looks at data rights through a feminist lens. Listing AI initiatives and start-ups across Africa, the site observes that most are based on facial recognition technologies, automated decision-making systems, machine learning and natural language processing.

Chair noted that narratives of AI across the continent tend to position it as a solution to various challenges. However, she warned, AI should not be uncritically embraced.

For example, while China’s facial recognition programmes in Zimbabwe have promised to inform less biased AI systems, some scholars argue that these countries may be giving away valuable data with disproportionate compensation.

According to the United Nation’s 2019 Digital Economy Report, China and the USA together currently account for 90% of the market capitalization value of the world’s 70 largest digital platforms. Europe and Africa lag with 3.6% and 1.3% respectively. The report warns:

“Countries at all levels of development risk becoming mere providers of raw data to [major global] digital platforms while having to pay for the digital intelligence produced with those data by the platform owners.”

Additionally, where data protection and cybersecurity policies don’t exist, external AI investment may pose a risk to humans rights, particularly in non-democratic states, argue AI researchers Arthur Gwagwa and Lisa Garbe.

On the other hand, mistrust of technology in some parts of Africa is discouraging local innovation, critical to bridging the widening inequalities in the digital economy. Community-based programmes such as the Rwanda digital ambassador programme, launched in 2017, are good ways of countering such mistrust, Ruttkamp-Bloem said.

“The model is that young people – postgrads and entrepreneurs – go into communities and provide digital illiteracy training… in local languages, focusing on locally relevant digital content and services,” she explained. The programme also helps to support women’s digital literacy by ensuring a balance of male and female digital ambassadors.

Strengthening regulatory frameworks

Despite promising AI initiatives across the continent, African voices remain notably silent in global debates on AI ethics, Ruttkamp-Bloem said. Emphasising that reasons varied across countries, she pointed to political instability and weak government structures; restricted movement; inequalities in education; lack of policy frameworks; and connectivity issues.

Based on a 2019 AI needs assessment survey, UNESCO recommended that African states foster legal and regulatory frameworks for AI governance, and enhance capacities for AI governance. Twenty-two countries had legal frameworks on personal data protection at the time the report was published.

The UNESCO report also pointed to the need for AI governance policy initiatives, such as AI policy toolkits. The HSRC has since produced a series of nine sectoral topical guides, which offer advice on AI and data governance and regulation in South Africa.

“We must not lose sight of the immense opportunity before us, to advance truly African values in regulating AI, whether this draws from African human rights jurisprudence that foregrounds the role of traditional communities and state sovereignty, or African systems of human ethics which centres the community.” said the HSRC’s Rachel Adams, speaking after the webinar.

As the leader of the Ethics of AI research group of the cross-university Centre for Artificial Intelligence in South Africa, Ruttkamp-Bloem said, “My main aim is to form a community of young people that can take AI ethics policy-making and research further in South Africa.”

‘Datavorous’ continent

Before we talk about AI, we must transform Africa into a ‘datavorous’ continent, argued Adekanmbi: a continent of systems, policies, and infrastructure to transform data into digital intelligence.

The UN’s Digital Economy Report underscores the strategic value of data, as the basis of all fast-emerging digital technologies, including AI, blockchain, the internet of things, cloud computing and internet services.

Currently, African states largely lack the capacity to harvest digital data. According to the UN report, Africa and Latin America together account for less than 5% of the world’s colocation data centres, where data is stored and processed.

Initiatives are springing up across the continent in response to this opportunity. For example, the Kenya-based Data Science Africa, established in 2015, is a hub connecting data scientists across Africa, and hosting debates on capacity building and data policy.

However, Adekanmbi warned, simply importing approaches to data-driven innovation will not work. Innovation must work on existing infrastructure, and use cases must align with the Sustainable Development goals in Africa.

Professor Elefelious Getachew Belay of the Addis Ababa Institute of Technology argued that creating societies that benefit from this data requires investing in African talent.

“Early education is key,” agreed Adekanmbi. One notable initiative of Data Science Nigeria is the free distribution of an innovative elementary school book that introduces the logic of coding to children.

“The book simplifies AI with cartoon characters which any kid can understand, using images language that are relatable, that are friendly [and] which are understandable, with an intention to build their curiosity, to start looking at problems around them, and asking, How can I solve them?”

In addition to the potential future contribution of its youth, Africa is important to the global AI narrative for another reason, Ruttkamp-Bloem and others have suggested: the pan-African concept of ubuntu offers an alternative philosophy for imagining and building a more equal future.

“AI will have a truly global impact. And managing it for the benefit of everyone requires international and cross-cultural collaboration and understanding,” Dr Kanta Dihal of LCFI said.

“[T]he African ethical collectivist paradigm may very well turn out to be the golden thread needed to weave together a sustainable global AI narrative,” said Ruttkamp-Bloem, “focused as it is on harmony, on shared human values, and the interconnectedness of all humans.”

Review by Andrea Teagle.

Andrea Teagle is a science writer at the Human Sciences Research Council, where she focuses on health, education, and development research news. She has worked as a journalist at several news outlets, including Quartz and the Daily Maverick, where she received the 2017 Discovery Young Upcoming Health Journalist award. She previously worked as researcher for the Rhodes University Centre for Health Journalism and the Health Economics and Epidemiology Research Office at Wits.

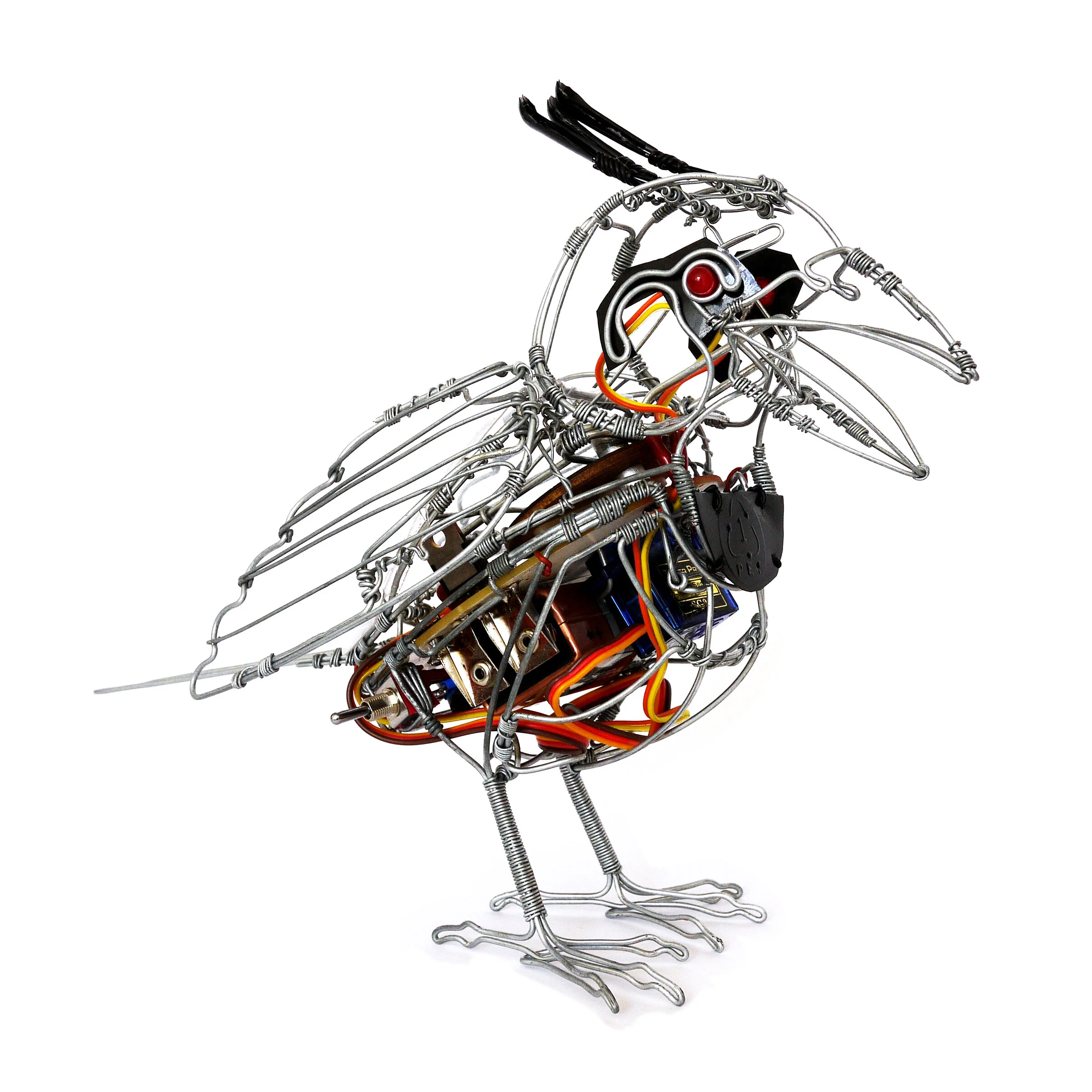

Image: Crested Barbet by africanrobots.net